According to Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department (Economy) Datuk Seri Mustapa Mohamed:

“The fourth quarter of the year (4Q20) is a lot more challenging in terms of mounting an economic recovery than initially expected“.

[Speaking at a fireside chat during the World Bank Group’s launch of the latest Malaysia Economic Monitor, the minister attributed the enhanced difficulty to a surge in coronavirus infections during the period]

see The Edge report 12/12/2020 below:

1] On 7th. November 2020, it was reported that World Bank Group lead economist Richard Record had indicated that Malaysia has already depleted much of its available fiscal space and would emerge from the current crisis with a larger burden of debt and contingent liabilities despite the debt ratio had been approved by Parliament to increase from 55% to 60% of the gross domestic product (GDP).

There would be difficult intertemporal constraints to further expand expenditures on relief and consumption-supporting stimulus over the near term.

This scenario shall leave national economy less endowed to invest in lasting recovery while maintaing growth in the future.

A paper published by the International Monetary Fund titled ‘Debt and Growth: Is There a Magic Threshold?’’ stated that countries with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 90 per cent and above could experience a dramatic decline in economic growth.

2] Even Moody Services had stated that the still-wide deficit for 2021 would increase the government’s fiscal consolidation challenge over the next few years. Further, any back-loading of efforts to reduce its debt burden over the year 2022 and 2023, will leave our national debt to the next generation of political leaders, and the present youth populace, to burden.

3] To finance the estimated deficit of between six and seven per cent, the national economy needs an increase in its borrowings beyond the self-imposed debt ceiling of 55 per cent of the GDP that have since upgraded to 60% by Parliament on 24th August 2020.

The country 2021’s concerns are focusing on how to foot the bill after a sovereign-rating downgrade earlier this month.

The government expects revenue to rise 4.2% next year, counting on higher tax collections — without raising taxes or introducing new ones — coupled with a move to slash its dependence on oil. The plan hinges on one key assumption: that tax income will rise as economic activity returns close to normal.

“If the economy does not recover as strongly as the 6.5%-7.5% that the government is expecting, any revenue shortfall is likely to manifest” in lower tax revenue, said Wellian Wiranto, an economist at Oversea-Chinese Banking Corp in Singapore, (theedge 22/12/2020).

4] A few local economists, in the financial institutions and stockbrokerage, their unsaid projection is that a 75% of GNP in the debt ceiling could only vindicate Sukhdave‘s pessimism paper on country’s slow growth rate and the ominous signs in the Post-1997 Political Economy paper.

5] However, empirical studies have revealed that the accumulation of external debt is typically associated with an increase in Malaysia’s economic growth up to an optimal level only. Any additional increase of external indebtedness beyond that specific level would inversely contributed to a detrimental national economy; as validated by World Bank sentiment as stated above.

This is thus likely scenario since Post-1997 period whence the growth rate had halved Malaysia economic performance since then. There were visible increases in flow of money in the economy as per Post-1997 Political Economy paper.

6] Since 1997, the country had relied extensively on these Malaysian Government Securities for budget deficit financing where part of the budget deficits was financed by creating or printing new

currency notes (“helicopters’ monies”).

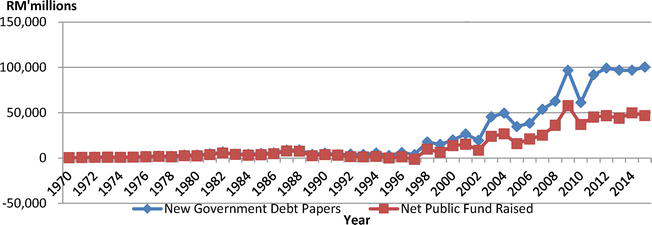

Also part of the debt papers was monetized; therefore, money supply and currency in circulation increased sharply since 1999, see Figures as per Mohamed Aslam and Raihan Jaafar paper.

Government issuance of new debit papers: floated upward in the AFC1997, then another splurge during dotcom burst 2001, followed by the GFC2018 spike that continued upward thence with “helicopters’ monies” circulating in the market.

7] In short, the amount of money floating around is not to generate wealth but within the circuit of financialization capitalism components of FIREs (finance, interests, real estate) are in furtherance of repaying mortgage loans, hire purchases, insurances, real estates tax dues and other debt interests.

8] Then, there is the leakage to outside the country through the estimated 5 million (2 millions registered and 3 million illegals) migrant workers who remitted their salaries homes; Rosli and Kumar had researched and written that already in 2006 the remittances made in the Malaysian economy amounted to ₤72M monthly (about RM$500 million every month, then).

Not only a large sum of money flows out of the country, migrant workers do not spend much locally to create a spread effect to contribute, and induce, economic growth; typically, a migrant worker would only spend MY$ 200 (₤29) monthly. This amount, if compared to a Malaysian’s monthly expenditure is very low; on average, the Malaysian locals spend MY$1,943 per month in urban areas and MY$1,270 in rural areas, (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2004/5).

The high percentage of immigrant construction workers exposes the country to high remittances that disturbs the economic cycle flow in the form of leakages (Mustapa and Pasquire, 2007; see Chart 1 below), thus tampering economic growth.

9] Mohamed Aslam and Raihan Jaafar had expressed budget deficits in macroeconomics terms of crowding out private investment, increasing interest rates, expanding money supply and escalating consumer price and in certain extent affect exchange rate.

Government bonds issued to finance budget deficits are also in question as part of the net wealth of private sectors. This is because if there is a continuous growth of debt, creditors may become concerned about the government’s initiative to repay it.

Over time, these creditors will expect higher interest payments to provide a greater return for their increased perceived risk as it is widely acknowledged that higher interest costs dampen economic growth.

10] COVID-19 has accentuated as never before the interlinked ecological, epidemiological, and economic vulnerabilities that the country is confronting without overcoming the structural political economy deformation arena wholesomely nor thoroughly in preceding economic crises:

Olin Liu

Malaysia: From Crisis to Recovery, IMF Occasional Paper No. 207, impressed:

The way forward should have include (continuing) structural reforms to achieve healthy balance sheets of the banking and corporate sectors and further deregulation to promote competition and efficiency.