1] INTRODUCTION

Khazanah Research Institute 2018 Report revealed that lower income households spent around 90% of their income on household expenses, but the higher income households only spent 45% of their income for the same essential items.

In fact, the top 20% of population – the T20 – possess 46.2% of the national income share, while M40 have 37.4% of the national income share but the bottom 40% of population – the B40 – only get 16.4% of the national income share of wealth.

The Covid-19 pandemic has reduced the nutritional necessities of the B40 households because their sources of income have been drastically cut.

The economic slowdown and resulting loss of jobs has affected the livelihoods of many poor families. They are finding it harder to put food on the table, let alone good quality, nutritious food.

In July 2020, the Department of Statistics, Malaysia (DOSM) announced it had revised the country’s Poverty Line Income (PLI) from RM980 to RM2,280.

This only come about after the UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights Phillip Alston said in August 2019 that Malaysia’s actual poverty rate could range from 15 to 20 per cent, despite official government data in 2016 placing it only at 0.4 per cent of households living below the poverty line.

If we go by the 2018 Bank Negara study, cost of living in Klang Valley is extremely high. BNM estimated living wages in Kuala Lumpur for singles, childless couples and couples with two children at RM2,700, RM4,500 and RM6,500 respectively.

Therefore, DOSM figures are not adequate for sustainable living in the low income groups. It is inevitable, at this time of a pandemic, the economic situations is really bad with the many, many food banks being operating in Kuala Lumpur, (see APPENDIX 1).

Through the years, the wages and salaries of Malaysian workers had grew less than 1%, or about RM17 in real terms, Bank Negara Malaysia data had shown. Even with a 4.2% GDP growth rate, it is belied by persistent joblessness which rose to 13% of employment in 2016, according to the central bank.

These sobering realities pose another enormous challenge to rakyat2 enduring struggle as their savings rate of 1.4% in 2013 is really razor-thin as reported by a Khazanah Research Institute (KRI) study in 2016.

Malaysia’s unemployment, which for the longest time hovered below 4%, spiked to 5% in April, 2020 and climbed further to 5.3% in May compared with 3.9% in March, 2020. This was the highest rate in 30 years since 5.7% in 1989. The official statistics revealed that there were 826,100 unemployed in May 2020 – an increase of 6% from 778,800 in April, 2020. In May, 2020: 47,000 more people became classified outside the workforce, pushing the total number of Malaysians not actively looking for work to 7.39 million, (theedgemarkets.com, 31/07/2020). Those not looking for work are school children, home carers and parents who have to stay at home to look after their schooling children during lockdowns. The 7.39 million constitutes three quarter of +10 million Malaysian workers including 1.5 million in government and non-government link companies as there are about 5 million registered and illegal migrant workers in the country.

(A CNBC report dated August 1st 2019: Malaysia had more than then 7 million foreign workers as part of a labour force of 15.5 million!)

By November 2020, the national unemployment is a high 764,400 persons without taking into accounts the underdevelopment figures! MOHE had indicated in mid-year 2020 that 41,161 out of 330,557 graduates in 2019 are still unemployed and with an addition of 2020’s 75,000, the total unemployment among this group is that at least 116,161 graduates still being unemployed.

Therefore, the Ministry of Finance’s (MoF) 2021 figure on the total unemployment rate of 3.5% or around 500K unemployed is extremely misleading, as there is often a backlog of those 21 public-sector universities and 38 private-sector universities producing something like 51,000 graduates a year, but nearly 60% remain unemployed one year after graduation, according to a study in 2018 conducted by the Minstry of Education Malaysia’s Graduate Tracer Study.

To those who are able to find jobs in the Gig-economy will not reduce the underemployment as well as those working under zero-hour contracts to generate private consumption which took a rather hard hit in 2020, already reduced by 4.2%.

A pause here.

Underemployment is labour utilization in the economy in terms of skills, experience and availability to work in a situation by which an individual is forced to work in low paying or low skill jobs.

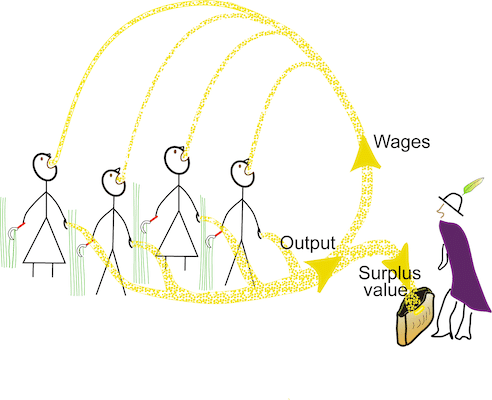

Workers under capitalism are compelled by their lack of ownership of the means of production to sell their labour power to capitalists for less than the full value of the goods they produce. Capitalists, in turn, need not produce anything themselves but are able to live instead off the productive energies of each and every worker effort.

This is labour exploitation.

767 million people, or 10.7% of the world’s population, live in extreme poverty, compared to some 42% of the world’s population in 1981. Though percentage has decreased, the numbers are still large.

Khazanah’s Professor Jomo had quoted a 987 million large figure.

Also, we must not only talk about poverty with hunger, but other aspects, too.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) deems other factors more relevant, such as living costs for Asia’s poor, food costs rising faster than the general price level, and vulnerability to natural disasters, climate change, economic crises and other shocks. Its estimated extreme poverty rate for Asia in 2010 thus increased by 28.8 percentage points to 49.5% while the estimated number of poor jumped by 1.02 billion to 1.75 billion people!

The UN Development Programme’s Human Development Report (HDR) publishes its Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) considering multiple deprivations across three dimensions – health (nutrition, child mortality), education (years of schooling, school enrolment) and living standards (cooking fuel, toilet, water supply, electricity, flooring, assets), see APPENDIX 2 on housing.

About 1.5 billion people in the 102 developing countries currently covered experience such acute deprivations. Close to 900 million people are vulnerable to falling into poverty following setbacks due to financial crisis, natural disaster and other factors.

3] TOWARDS A POVERTY ERADICATION INITIATIVE

Selective new thinking on poverty and its eradication (see Appendix 3) is summarized as follows:

• Dominant mainstream perspectives have often led to poor, ineffectual policy prescriptions.

• Poverty reduction has to be helped by sustained growth of output and decent jobs.

• Growth helps to raise incomes to raise additional resources for more social spending in education and public wellbeing.

• Growth needs to be more stable, with consistently counter-cyclical macroeconomic policies and better capacity to deal with exogenous shocks.

• Progressive structural change and inequality reduction are very crucial for development.

• Social provisioning pushes forward to accelerate development and poverty reduction.

• Social protection can better mitigate negative shocks, prevent people becoming much poorer, and help generate economic activities and livelihoods.

• A basic social protection floor is affordable in most countries, although poorer countries will progress faster with donor support.

APPENDIX 1

_______

Cases of poverty faced by workers

Case 1

Speaking to CNA at a public housing apartment designated for the hardcore poor, a wirker said that her household income is only RM1,300 a month from her husband’s job as a school bus driver.

“It’s a struggle every month, and I’ve tried applying for eKasih, the federal government’s welfare programme, but I never heard anything from them until I got frustrated,” Mdm Janaki claimed.

Case 2

In urban areas, the poverty incidence was 3.8 per cent, compared with rural areas at 12.4 per cent, a Mr Mustapa said.

Case 3

“It’s a difficult time for me now because we have to cut down on our grocery expenses,” said Firdaus, who is married with a young child. “We have to ration our meals like it’s war time.”

Case 4

Voon is thankful that he has a part-time job as a university lecturer to fall back on as he looks for a full-time gig.

However, some of his former colleagues are less lucky as they do not have an alternative source of income.

A Malay lady named Siti Noor Madzariah came to MP Teresa Kok’s service centre to ask for food. She looked very desperate and hungry.

“I then came out and have a chat with her. She said she was a former cabin crew of Malaysia Airlines (MAS). After she was retrenched by MAS 6 years ago, she couldn’t find a proper and permanent job. She has to feed 5 kids at home. She told me she did not have money to feed them.

She said she stayed in Sri Manja at Jalan Klang Lama. She was unable to pay rental and installment of her motorbike.”

Teresa Kok then gave her some food and gave her RM300.

Siti took Teresa gifts and burst into tears. “She knelt down before me and touched my feet and thanked me many times.” Teresa was shocked to see her reaction.

Teresa told Siti that she will try to ask around to get her a job. Siti was very excited to hear this. “She said she can do any job, and can even work as cleaner or waitress in restaurant. She then asked me whether she can start working tomorrow. Aiduh! ….“

Teresa felt very sad to see this hungry woman; her Service Centre staff had said that there were many desperate people like this coming to the centre to ask for food and money lately.

Teresa got the permission of Siti to put our photo and her appeal for a job in FB: “If anyone of you wish to give her some assistance or help to find her a job in my constituency, please contact my service centre at 03-7983 6768. #Kitajagakita.”

Jeyakumar Devaraj writes:

Renuka: RM300 per month. We could manage before the MCO [movement control order] but my husband lost his job. He has been trying everywhere, but he cannot get a job. Now he is doing odd jobs like painting houses for Deepavali. But it’s not enough.

Me: Do you work?

Renuka: I have four children. The eldest is 13 and the youngest is five years old. I stay at home and look after the family.

Me: You should have got the BPN [Bantuan Prihatin Nasional or National Caring Aid] last week. RM700, I think. Can’t you use that for the rent?

Renuka: The ATM card is with the money lender. My husband borrowed RM2,000 a few months ago and gave the ATM card as surety. The money lender will withdraw RM500 each month and give us the remainder. As we did not make loan payments for a few months, all the BPN money was taken by him.

Me: How much is the outstanding loan amount now?

Renuka: About RM2,900 I think. Have to ask my husband.

Me: How come RM2,900 when you only borrowed RM2,000?

Renuka: Interest is 10% per month. If we cannot pay, then RM200 is added to the principal.

Me: Can you get a family member to settle the entire amount? Then you just have to settle the principal with the family member.

Renuka: If we had a family member who could do this, we would not have gone to the money lender, sir.

Me: Can I get someone from my Service Centre to visit your house?

Renuka: Can.

This is the reality for families in the bottom 20% of households in our society. They are in a desperate position.

The BPN idea is good. But families like this one need more of it and on a regular, monthly basis. Otherwise, they will be forced to go to the money lenders and get entrapped there.

This is why the PM is proposing a more targeted cash transfer programme – RM1,000 monthly for families with a monthly household income of less than RM1,000.

We estimate that 10% of the 7.3 million households in the country will require this assistance: 730,000 families x RM1,000 per family would be RM0.7bn per month. This works out to RM8.7bn for the entire year. This is a sum the country can afford, and it will be a lifesaver for families like Renuka’s.

Source: https://aliran.com/thinking-allowed-online/a-disturbing-conversation/

APPENDIX 2

POVERTY IN HOUSING AND POORS FOR SHELTERS

The Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) released figures to show that the average monthly salary and wage received by workers in the country was RM3,224 in 2019; a typical apartment in the Klang Valley is one hundred times say on this basic monthly salary. Presently, there is a total of about 10 million salary and wage recipients in Malaysia.

The Household Income & Basic Amenities Survey Report 2019 by DOSM showed that the country’s 2019 median income of a household of four is RM5,873. This means it is sixty times of both parents’ monthly salaries to get a decent shelter.

Between 2010 and 2019, in the country, the average y-o-y height of increase in house prices was 7.9% surpassing income’s increment of only 5.6%.

According to VPC Alliance (KL) Sdn Bhd managing director James Wong, Khazanah Research Institute (KRI) defines housing affordability as a function of both house prices and income, and a yardstick of “affordable” is a median multiple of 3.0 times.

By applying the median household income 2019 published by DOSM and the affordable housing range based on KRI’s calculation of 3.0 times the median multiple, affordable house prices in most states are lower than the median house price. It appears that house prices are not within the affordability of the household, except for Putrajaya and Melaka, where at the former precinct many government officers reside. If one is not owning a house, a room rental costs at least four times more nowadays while salary has not moved much once inflation is factored in, according to a tenant.

For more details indicating the issues, identifying the problems, and investigating the dimensions of housing and shelters for the underprivileged segment of our Malaysia society, go to:

APPENDIX 3

Unfulfilled : Malaysia’s Cost of Living Challenges

THE WORLD BANK REPORT

OCTOBER 29, 2020

In Malaysia, perceived increases in the cost of living have been a subject of ongoing debate and discussion, despite the country’s current period of low and stable inflation. Rather, the “cost of living” is frequently used as a catchall term that reflects wider impacts on household budgets and individual well-being beyond price increases. As such, concerns about the rising cost of living are influenced by several factors.

These include:

Large differences in living costs across different parts of the country

• Housing prices have the most notable difference across states and urban/rural areas, but large price differences for food, clothing, services, and other necessities also exist across geographical locations.

• Johor, Kuala Lumpur and Selangor are the most high-cost states, with lower living costs in Kedah, Kelantan and Perlis.

Income growth not keeping up with Malaysians’ expectations

• Younger workers face stagnant growth in employment income despite rising education qualifications. Wage growth is also sluggish for those without higher education, regardless of age.

• Widening absolute income gaps between the bottom 40 percent and the top 20 percent of the income distribution have also furthered the sentiment of being left behind.

Low savings and heavy debt burdens

• A majority of households do not have adequate financial savings, and financial pressures are felt by most working adults regardless of age group and location.

• Debt among lower-income borrowers is mostly used to support consumption, either for motor vehicle or personal financing loans, rather than longer-term investments to accumulate wealth.

Deteriorating housing affordability in Klang Valley

• The supply of affordable housing does not meet demand in key urban areas such as Kuala Lumpur and Petaling District.

• The shortage of affordable housing is most severe for households earning between RM3,000-RM5,000 per month.

• Overcoming these challenges requires a mix of short-term measures to ease immediate cost of living pressures, coupled with longer-term structural reforms to boost market competition and increase incomes.

Short-term measures:

• The creation and timely reporting of an official Spatial Price Index (SPI) will help create policies to address price increases in different areas, providing better alignment to B40 consumption patterns.

• Expanding childcare services and flexible working arrangements for B40 families to make it easier for parents to participate in the labor force.

• Creating a repository of accessible financial planning tools for all.

• Adopting a more precise housing affordability measure, which considers location, housing supply and demand, instead of relying mostly on median incomes and home prices.

• Strengthening the rental market through a Rental Tenancy Act and Tribunal.

Medium and long-term measures:

• Realigning investment and hiring incentives toward high quality job creation.

• Expanding early childhood education and promoting life-long learning and upskilling.

• Strengthening consumer protection and encouraging more responsible behavior by banks and other financial institutions.

• Increasing financial incentives to encourage retirement savings.

• Prioritizing low- and middle-income households in housing policies and programs.

• Strengthening coordination across federal, state, and local governments in housing policies and planning.